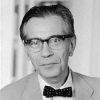

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadterwas an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century. Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier approach to history from the far left, in the 1950s he embraced consensus history, becoming the "iconic historian of postwar liberal consensus", largely because of his emphasis on ideas and political culture rather than the day-to-day doings of politicians. His influence is ongoing, as modern critics profess admiration for the grace of his...

NationalityAmerican

ProfessionHistorian

Date of Birth6 August 1916

CountryUnited States of America

Richard Hofstadter quotes about

To be sick and helpless is a humiliating experience. Prolonged illness also carries the hazard of narcissistic self-absorption.

The delicate thing about the university is that it has a mixed character, that it is suspended between its position in the eternal world, with all its corruption and evils and cruelties, and the splendid world of our imagination.

Intellectualism, though by no means confined to doubters, is often the sole piety of the skeptic.

Whatever the intellectual is too certain of, if he is healthily playful, he begins to find unsatisfactory. The meaning of his intellectual life lies not in the possession of truth but in the quest for new uncertainties.

The intellectual ... may live for ideas, as I have said, but something must prevent him from living for one idea, from becoming obsessive or grotesque. Although there have been zealots whom we may still regard as intellectuals, zealotry is a defect of the breed and not of the essence.

It is a part of the intellectual's tragedy that the things he most values about himself and his work are quite unlike those society values in him...

It is possible that the distinction between moral relativism and moral absolutism has sometimes been blurred because an excessively consistent practice of either leads to the same practical result — ruthlessness in political life.

The tradition of the new. Yesterday's avant-gard-experiment is today's chic and tomorrow's cliche.

As with the pursuit of happiness, the pursuit of truth is itself gratifying whereas the consummation often turns out to be elusive.

Anti-Catholicism has always been the pornography of the Puritan.

We have learned so well how to absorb novelty that receptivity itself has turned into a kind of tradition- "the tradition of the new." Yesterdays avant-garde experiment is today's chic and tomorrows cliche.

The intellectual is engage-he is pledged, committed, enlisted. What everyone else is willing to admit, namely that ideas and abstractions are of signal importance in human life, he imperatively feels.

Intellect needs to be understood not as some kind of claim against the other human excellences for which a fatally high price has to be paid, but rather as a complement to them without which they cannot be fully consummated.

The utopia of the Populists was in the past, not in the future. According to the agrarian myth, the health of the state was proportionate to the degree to which it was dominated by the agricultural class, and this assumption pointed to the superiority of an earlier age.