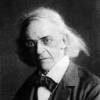

Theodor Mommsen

Theodor Mommsen

Christian Matthias Theodor Mommsenwas a German classical scholar, historian, jurist, journalist, politician, archaeologist and writer generally regarded as one of the greatest classicists of the 19th century. His work regarding Roman history is still of fundamental importance for contemporary research. He received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1902 for being "the greatest living master of the art of historical writing, with special reference to his monumental work, A History of Rome", after having been nominated by 18 members of...

NationalityGerman

ProfessionNon-Fiction Author

Date of Birth30 November 1817

CountryGermany

When the Romans in the last age of the republic came into immediate contact with Iran as a consequence of the occupation of Syria, they found in existence the Persian empire regenerated by the Parthians.

When Sulla died in the year 676, the oligarchy which he had restored ruled with absolute sway over the Roman state; but, as it had been established by force, it still needed force to maintain its ground against its numerous secret and open foes.

The order of things established by the Romans in Libya rested in substance on a balance of power between the Nomad kingdom of Massinissa and the city of Carthage.

The Dalmatian tribes and the Pannonians, at least of the region of the Save, for a short time obeyed the Roman governors; but they bore the new rule with an ever increasing grudge, above all on account of the taxes, to which they were unaccustomed, and which were relentlessly exacted.

In the Roman commonwealth, even on the conversion of the monarchy into a republic, the old was as far as possible retained.

For a whole generation after the battle of Pydna, the Roman state enjoyed a profound calm, scarcely varied by a ripple here and there on the surface.

We have no information, not even a tradition, concerning the first migration of the human race into Italy. It was the universal belief of antiquity that in Italy, as well as elsewhere, the first population had sprung from the soil.

To acquire possession of Latium was of the most decisive importance to Etruria, which was separated by the Latins alone from the Volscian towns that were dependent on it and from its possessions in Campania.

The power which the Hellenes and even the Italians possessed, of civilizing and assimilating to themselves the nations susceptible of culture with whom they came into contact, was wholly wanting in the Phoenicians.

The Phoenicians are entitled to be commemorated in history by the side of the Hellenic and Latin nations; but their case affords a fresh proof, and perhaps the strongest proof of all, that the development of national energies in antiquity was of a one-sided character.

The language of the land in the Parthian empire was the native language of Iran. There is no trace pointing to any foreign language having ever been in public use under the Arsacids.

The defeat of the Augustan policy, as the peace with Maroboduus and the sufferance of the Teutoburg disaster may well be termed, was hardly a victory of the Germans.

The Celtic, Galatian, or Gallic nation received from the common mother endowments different from those of its Italian, Germanic, and Hellenic sisters.

Little do we find any Phoenician architecture or plastic art at all comparable even to those of Italy, to say nothing of the lands where art was native.